A great photo of the Monadnock Building from The Man on Five Tumblr.

John Jacob Glessner House, 1800 S. Prairie Avenue (1887-Present)

John Jacob Glessner House, 1800 S. Prairie Avenue (1887-Present)

The sturdy, Romanesque Glessner house was designed by architect Henry Hobson Richardson as a winter residence for farm implement manufactuer John J. Glessner.

Despite its cold, fortress-like exterior, the home’s interior is trimmed in warm woods, outfitted with custom furniture and fabrics, and features a secluded, south-facing interior couryard to capture maximum sunlight.

While many other Prairie Avenue mansions succumbed to the decline of the neighborhood, Glessner House remained well-kept until the preservation movement began to rescue valuable landmarks from the wrecking ball. The property was named a Chicago Landmark on October 14, 1970, listed in the National Register of Historic Places on April 17, 1970, and recognized as a National Historic Landmark on January 7, 1976.

The non-profit Glessner House Museum is open to the public.

Sources: AIA Guide to Chicago, Wikipedia.

Photos Courtesy Library of Congress.

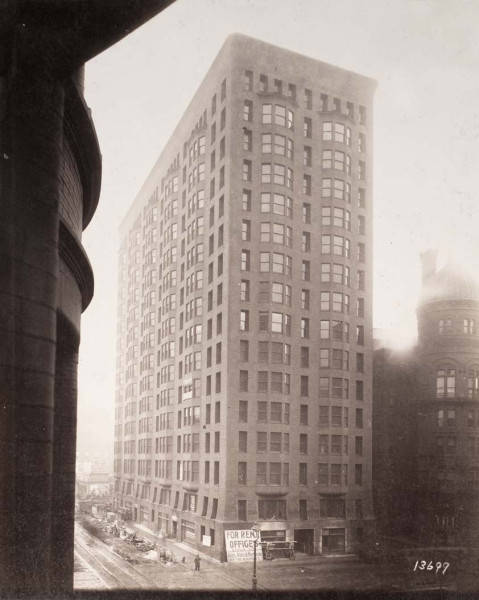

Standard Oil of Indiana Headquarters, 910 S. Michigan Ave. (1911-Present)

Standard Oil of Indiana Headquarters, 910 S. Michigan Ave. (1911-Present)

The Chicago-based Karpen Brothers Furniture Company was the largest upholstered furniture company in the world in the early part of the 20th Century, and in 1911 they commissioned a headquarters for their offices and manufacturing at 910 S. Michigan. The nine Jewish immigrant brothers from Prussia had taken over the former location of the opulent Richelieu Hotel at 318 S. Michigan Avenue and converted it into their main factory in 1899. The Richelieu was famous for bringing fine dining to Chicago, but had lost money since its opening in 1885, and went into recievership in 1895. But by 1911, the Karpen Brothers had outgrown their six-story building just south of the Art Institute.

Also in 1911, the federal government broke apart John D. Rockefeller’s powerful Standard Oil Trust– which held 80% of market share in the growing oil industry– into several smaller companies, one of which was Standard Oil Company of Indiana. In 1927, the Karpen Brothers sold the 13-story building, designed by Blackstone Hotel architects Marshall & Fox, to Standard Oil. Seven more stories were added to the building by architects Graham Anderson Probst & White in 1927, about the same time as the completion of the massive Stevens Hotel, just two blocks north on Michigan Avenue.

In the 1920s, oil companies became even more powerful with the boom in personal automobile ownership after World War I. On November 17, 1921, a group of wealthy and politically connected oilmen met in a hotel room in New York City to orchestrate what would eventually become the Teapot Dome scandal. The group included Colonel Robert W. Stewart, chairman of the board of the Standard Oil Company of Indiana. The group set up a dummy corporation in Canada, called the Continential Trading Company, which made a $3 million profit of which Stewart got $760,000.

When the scandal became known, Stewart at first escaped to Cuba, but returned to stonewall a Senate investigating committee. He was eventually tried for contempt of the Senate and perjury, but was acquitted both times. Under pressure to punish Stewart, the Rockefeller family– with a 15% stock interest in Standard Oil of Indiana– forced Stewart out of his $125,000 per year job with Standard Oil of Indiana, but Stewart ended up with a golden parachute pension of $75,000 per year.

Through the 1950s the roof of the building supported a 70 foot by 76 foot Standard Oil logo facing Lake Shore Drive. In 1956 the sign was touted as the largest neon emblem in the United States. In the mid-1950s, the Standard Oil Company had nearly 2000 daily employees working in the building, served by 14 elevators with 17 elevator operators. A restaurant at the south east corner of the ground floor served over 3000 meals per day.

In 1973, Standard Oil moved their headquarters to the 82-story Standard Oil Building (now the Aon Center) at 200 E. Randolph, leaving their former home to struggle to find office tenants at a low point in South Loop development. The State of Illinois used the building for several years through the 1970s and early 1980s as offices for the Department of Employment Security. But by 1986 the building was nearly vacant.

Villas Development Corporation purchased the building in 1994 as the surrounding neighborhood was near bottom, and attempted the largest office-to-residential conversion in Chicago real estate history. After many false starts, delays and difficulties, the building was opened as loft condominiums with commanding views of Grant Park and Lake Michigan in 2000, under the name Michigan Avenue Lofts. One of the most attractive atributes of the building is the south-facing 65-foot by 65-foot light court. A $1 million wood-paneled lobby was installed to give the building some much-needed warmth.

The residents of the building are a proud and tight-knit group of urban pioneers. On June 4, 2011, more than 100 residents, neighbors and members of the Karpen family gathered in the building to celebrate the building’s 100th anniversary with speeches, music, and a gala dinner.

Sources: Emporis, AIA Guide to Chicago, American Heritage.com, Wikipedia, Chicago Department of Landmarks, SKarpenFurniture.com, New York Times; January 29, 1899, Helene Gabelnick, John Taylor, Chicago Journal.

Written by John C. Thomas

First African-American Catholic Priest

Father Augustine Tolton: First African-American Catholic Priest

Father Augustus Tolton (April 1, 1854-July 9, 1897)

John Augustine Tolton was born a slave in Brush Creek, Missouri on April 1, 1854. His mother, left alone with John and his two siblings after his father escaped to join the Union Army, led the family across the Mississipi River to freedom in Quincy, Illinois in 1862.

Eight year old John, hungry and poorly dressed, was noticed by Father Peter McGirr, Pastor of St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Quincy. Offering to work for food, Father McGirr gave him a meal asked him if he wanted to attend St. Peter’s Catholic school.

Young John excelled in school, and Father McGirr asked him if he wanted to become a Catholic. John was baptized soon afterward, and studied with Father McGirr for his Holy Communion. After serving a summer as Alter Boy for the 5 a.m. mass, Father McGirr asked young John if he would like to become a priest—the first African-American priest in the United States. Amazed, but eager to embark on the 12 years of difficult study, the two prayed for his success.

After high school, John attended and graduated from Quincy College. Denied entry to enter an American Catholic Seminary, Father McGirr and a group of Franciscan Fathers assisted with the arrangements for John to study in Rome. At age 32, John Augustine Tolton was ordained a Catholic Priest in Rome by Lucindo Cardinal Parochi on April 24, 1886.

Fr. Augustus Tolton returned to the United States to a hero’s welcome on July 6, 1886 and offered his first Mass on American soil to the mostly Black congregation at St. Benedict the Moor parish church in New York City. He also presided over Mass for the Franciscan Sisters at Hoboken, New Jersey.

Father Tolton returned to Quincy on July 17, 1886. As the train pulled into town, a band played “Holy God” as the crowd of all colors cheered. A decorated carriage drawn by four white horses took him through the streets to Saint Peter Church where an even another crowd had been waiting.

Father Tolton returned to Quincy on July 17, 1886. As the train pulled into town, a band played “Holy God” as the crowd of all colors cheered. A decorated carriage drawn by four white horses took him through the streets to Saint Peter Church where an even another crowd had been waiting.

On July 25, 1886, Father Tolton was formally installed as pastor at the Negro Church of Saint Joseph in Quincy, and began his pastoral work. The Quincy Journal had high praise for Father Tolton, citing his “fine educational training,” “wholehearted earnestness,” and “a rich voice which falls pleasantly on the ear.”

Meanwhile, African-American Catholics began arriving in Chicago during the Civil War. They formed the St. Augustine Society in the early 1880s to visit the sick, feed the poor, and bury the dead. As their reputation and numbers grew, they desired to form a congregation of their own.

In 1889, the St. Augustine Society requested Bishop Foley to secure Rev. John Augustine Tolton, first African-American priest ordained for the United States, as their spiritual director. Father Tolton had been experiencing some racial resentment from priests at another parish, and decided that starting a new parish and building a new church in Chicago would be a good move. He wrote to the Rome on September 4, 1889, “I beg you, give me permission to go to the diocese of Chicago. It is not possible for me to remain here any longer with this German priest.” A few weeks later, he made another request adding, “There are nineteen Negroes here whom I have baptized and they will follow me to Chicago. I will go at once, as soon as I receive your consent.” On December 7, 1889, Father Tolton received approval. He arrived in Chicago on December 19, and found a room at 2251 South Indiana Avenue, about a mile and a half from St. Mary’s Church at 9th and Wabash.

Fr. Tolton began ministering to the small congregation of 30 parishioners in the basement of St. Mary’s Church while working to establish his own parish. Under Fr. Tolton’s leadership, The St. Augustine Society sought donations to establish their own church. In 1891, Mrs. Anna O’Neill donated $10,000 for the building, which was to be named St. Monica’s.

Construction was started on a grand church for St. Monica’s parish, and by the time St. Monica’s opened at 36th and Dearborn in 1893, Fr. Tolton was ministering to six hundred parishioners.

Returning from the annual retreat of Chicago priests in Bourbonnais, Illinois on July 9, 1897, Fr. Tolton was overwhelmed by the 105-degree heat. He collapsed near Calumet Avenue as he walked to his rectory from the train station at 35th Street and Lake Michigan. He was taken to Mercy Hospital, but passed away four hours later from sunstroke. Father Augustus Tolton is buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery near Quincy, Illinois.

Links: Biography and photos of grave site at FindAGrave.com

Sources: St. Elizabeth Catholic Church in Chicago, “They Called Him Father Gus,” by Father Roy Bauer, Pastor, St. Peter Church, Quincy, Illinois

Photos: Holy Angels Church Chicago

2014 in review

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2014 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

A San Francisco cable car holds 60 people. This blog was viewed about 1,000 times in 2014. If it were a cable car, it would take about 17 trips to carry that many people.

Dearborn Station, 47 W. Polk St. (1885-Present)

Chicago’s oldest existing train station was designed by architect Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz in 1885. The original clock tower was a Flemish design that stood at the south end of Dearborn Street until a 1922 fire destroyed the tower and the hipped roof of the station. It was replaced by the current Romanesque design and a flat roof in 1923.

Dearborn Station, also known as Polk Street Station, was built for the Chicago & Western Indiana Railroad at an estimated cost of $400,000-500,000. In 1887, the station became the Chicago hub for the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. The station also was host to the Wabash, Grand Trunk, Monon Route, Erie, and Chicago & Eastern Illinois railroads among others.

In 1899, the station was host to 25 railroad lines, 122 trains, and approximately 17,000 passengers per day. By 1967 automobile and airline travel had diminished railroad travel to such an extent that the Santa Fe Railroad eliminated three of its seven daily departures from the station, and four of the five other tennants ended most of their daily runs. Santa Fe railroad service continued at the station until Amtrak moved remaining passenger operations to Union Station on May 1, 1971.

Above: The demolition of the Dearborn Station train shed in May 1976. The Lee jeans advertisement on the building to the left is still visable 35 years later. The area once occupied by the train shed is now a park in the Dearborn Park development.

In 1976, Dearborn Station’s acres of approach tracks and its giant train sheds were demolished to make way for a new and experimental concept in urban renewal known as Dearborn Park. The heavily landscaped mixture of townhouses, mid rises, and high rises was based on a master plan created by architects Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. The irreplaceable Dearborn Station was named to the National Register of Historic Places on March 26, 1976 and subsequently transformed into a shopping galeria and offices with 120,000 square feet of leasable space.

Sources: AIA Guide to Chicago, Dearborn Station, Wikipedia.

Sources: AIA Guide to Chicago, Dearborn Station, Wikipedia.

Photos Courtesy Wikimedia, Library of Congress, John C. Thomas.

Written by John C. Thomas

Additional Reading:

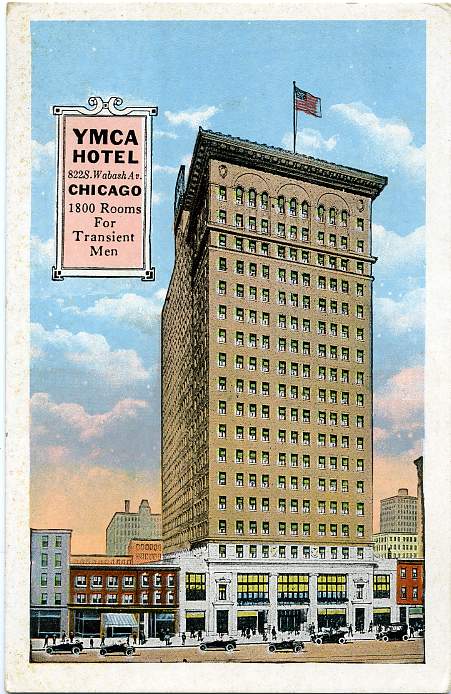

YMCA Hotel 826 S Wabash Ave. Chicago, IL

YMCA Hotel, 826 S. Wabash Ave. (1916-Present)

Similar to the YWCA almost exactly one block to the east, the YMCA Hotel was built to provide a safe, inexpensive and morally upright place for young men arriving in Chicago by the thousands every year. Designed by architect Robert C. Berlin and James Gamble Rogers, the hotel opened with 1800 small, simple rooms in 1916. Just 10 years later, a significant expansion of nearly 50% to the south of the original building expanded the number of rooms, the public areas, dining facilities, and recreational facilities.

The onset of The Great Depression saw the advent of aggressive marketing of the low cost, simple lodgings at the YMCA Hotel to a broader range of customers beyond single white men. Early 1940s marketing brochures and postcards touted the convenient location of the hotel for families and tourists.

As the surrrounding neighborhood declined following World War II and increased prosperity gave tourists better options, the hotel could not compete with Chicago’s more traditional lodgings and attracted an increasingly downscale clientele. A 1979 article in the Chicago Tribune marking the closing of the hotel proclaimed it a white elephant not suitable for renovation.

Yet by 1985, nearby urban redevelopment projects were taking off. Printer’s Row and Dearborn Park– pioneering urban residential redevelopments just a few blocks away– were starting to change the financial prospects of large urban residential projects. Also in 1985, the nearby Chicago Hilton and Towers was gutted and redeveloped to modern standards. Urban loft living was beginning to take hold in large cities, and the hotel’s proximity to downtown Chicago was again becoming its chief asset.

The entire building was gutted and turned into large, spacious loft-style apartments in 1985, complete with a rooftop deck, penthouses, and an attached theater and office complex. While the new Burnham Plaza took several years to gain a foothold, the eventual success of the project gave a tremendous boost to the South Loop and helped to spur similar projects at 888 and 910 S. Michigan.

HINKY DINK

Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna (1858-1946)Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna was Alderman, and then Committeeman, of Chicago’s First Ward from 1897 to 1946. The diminutive Kenna began his career as a newsboy in 1868, and eventually purchased a loop newsstand that became exceedingly successful.In the late 1800s, Hinky Dink purchased a tavern on Clark Street called The Workingman’s Exchange, where he traded food and alcohol for votes. Kenna was elected Alderman in 1897, when he teamed with fellow First Ward Alderman (each ward had two Aldermen until 1923) “Bathhouse” John Coughlin to create a powerful political machine in what was then called The Levee District, the area just north of 22nd Street along the east bank of the Chicago River. Hinky Dink and Bathhouse John meted out favors and indulgences in return for power, without any regard for morality or propriety. By the early years of the 20th Century, the Levee had become a haven for brothels and taverns, and the First Ward’s amoral fiefdom had crossed the line into a veritable pageant of political corruption. Each year, the pair would hold a lavish ball for the prostitutes, gamblers, bribing businessmen, and shady characters of their district, raising as much as $50,000 in tribute to their protection. By 1908, the First Ward Ball had become so brazen and notorious that newspapers from around the country reported on the open display of debauchery in America’s fastest-growing city. And reformers, concerned about Chicago’s reputation, began to pressure political leaders to put an end to the annual celebration of Chicago’s political corruption. On December 13, 1908, a bomb detonated at the Chicago Coliseum, where the First Ward Ball was to be held less than two weeks later. Hundreds of windows in the area were broken, and two workers preparing for the event were feared buried in rubble. But the event went on as planned. Sustained public pressure prompted Chicago Mayor Fred Busse to put an end to the soiree the following year. In 1923, additional reforms reduced the number of Chicago aldermen per ward from two to one, and Kenna left the city council to his partner Coughlin. Kenna won election as First Ward Committeeman that year, an influential political post paid for by the political party. He remained First Ward Committeman until his death in 1946 at age 89. For 34 years, Kenna and his wife lived in a third floor corner apartment overlooking Michigan Avenue and Grant Park in the Bucklen Flats apartment building (now the site of the Essex Inn Hotel at 800 S. Michigan). The once-luxurious apartment house– one of the first multi-story buildings along the Michigan Avenue streetwall– was demolished in 1933 for inability to pay property taxes. Kenna left an estate of over a million dollars, and bequeathed $33,000 for a mausoleum to honor his legacy. But instead– perhaps in an ironic nod to heredity– his heirs divided his memorial money and left him with an $85 tombstone. *Written by John C. Thomas Sources: New York Times, Wikipedia, Abbott, Karen: Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America’s Soul |

The South Loop in Chicago’s Film Legacy

The South Loop has had a starring role in Chicago’s film legacy, from the first film ever shown in Chicago to serving as the major film distribution point for the Midwest to training the actors and directors of the future. This video was written, directed and narrated by John C. Thomas.

Revisiting 1968 Dem Convention in Chicago with Mike James

Mike James was on the street when the 1968 riots occurred. in Chicago An SDS national council member, James leads a walking tour of the Grant Park battleground in downtown Chicago across from hotel headquarters of convention delegates and party candidates. This was the still-remembered event that despoiled the reputation of Chicago. The government’s Walker Commission later described it as a “police riot,” with more than 1,000 citizens and journalists were injured by police. The FBI was later identified as the outside agitator putting Chicago police “on edge” with catastrophic theories of the collapse of America from “hippies and demonstrators.” Many middle-class bystanders were beaten bloody by police who appeared in a trancelike state. The government Walker Commission described it as a “police riot.” For more videos from Michael James, visit youtube.com/heartlandmedia